Beginning, middle, and end part 7: Event stories

Summary: The key change in an event story about the protagonist’s situation and circumstances. The beginning introduces an outward goal, the middle shows the struggle to obtain it, and the ending shows success or failure.

“What do you need, to start a story? You need change . . . How do you build the beginning of a story around change? You need four things: (1) An existing situation. (2) A change in that situation. (3) An affected character. (4) Consequences.”

— Dwight Swain (Swain, Page 138)

Event stories revolve around achieving some kind of outward goal, like possessing an object, gaining the affections of a romantic interest, winning a tournament, or defeating an enemy.

- The key change in an Event story is about the situation and circumstances of the protagonist. (Kowal)

- The emotional fulfillment audiences derive is the thrill of doing adventurous things and overcoming obstacles to achieve success. (Kowal)

- The key turning points are external disasters (and rescues).

Recap

This note is a part of a series.

- Aristotle misinterpreted

- In search of a useful framework

- Story types

- Idea stories

- Character stories part 1

- Character stories part 2

- Event stories

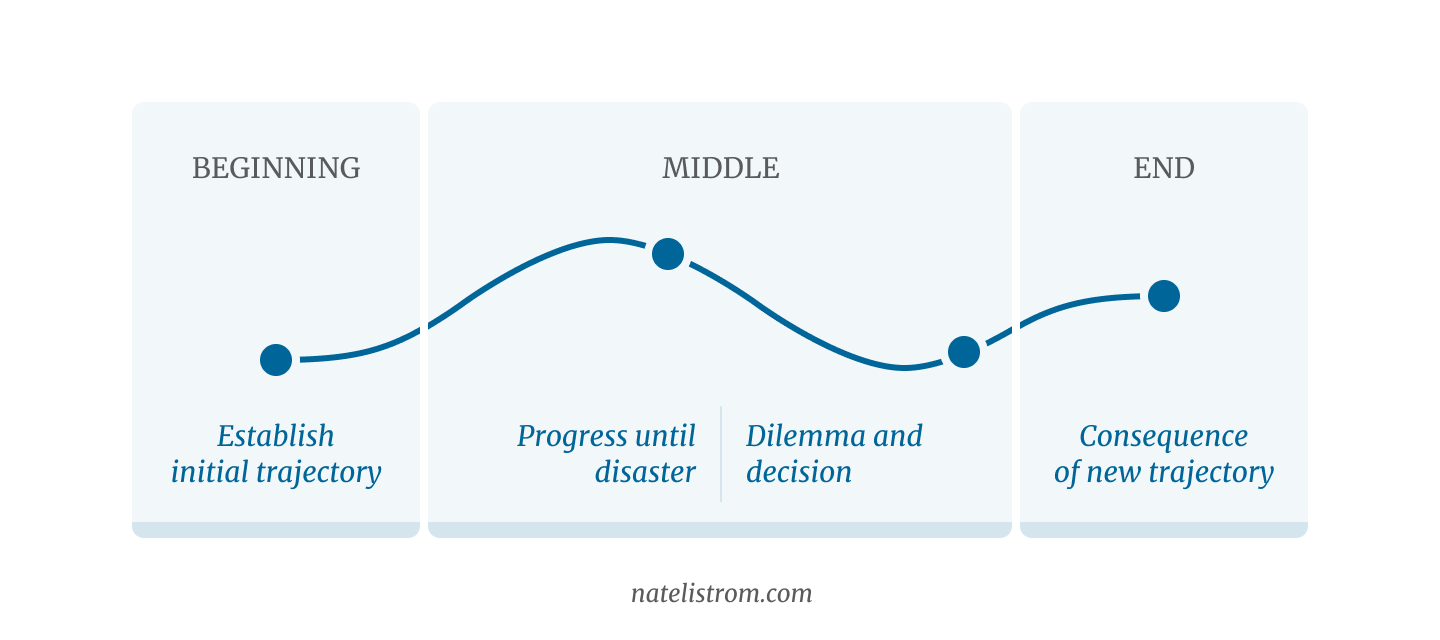

In the past six notes, we’ve been trying to develop a useful structural framework based on Aristotle’s “beginning, middle, and end.” Aristotle’s definitions give us clarity for the beginning and end, and we’re using Dwight Swain’s scene-sequel format to fill in the middle.

Here’s what that looks like:

| Beginning |

|

|---|---|

| Middle |

|

| End |

|

In this, last of the seven notes, we’ll finally turn our attention to Event stories.

Does our framework fit an Event story?

Beginning: forming a goal

Aristotle defines the beginning as “that which does not itself follow anything by causal necessity, but after which something naturally is or comes to be.” (Aristotle, Part VII) In our terms, it’s the “beginning of causality.”

In an Event story, the beginning of causality is about inspiring the protagonist to form an outward goal. She must want something specific in the external world, and the beginning of the story must show what event causes the formation of that goal.

In story theory discussions, this moment is often referred to as the “Inciting Incident.” I like to get a bit more specific. I think of it in terms of two key story beats, the “Call to Adventure” and the “Decision to Cross the Threshold.”

- The Call to Adventure is the first moment when some situational change confronts the protagonist in a way she cannot ignore. Her circumstances shift out of their previous alignment, and she is forced to respond.

- The Decision to Cross the Threshold is the protagonist’s commitment to do something about the change. This solidifies her goal and results in a plan to achieve it.

Star Wars: A New Hope

In George Lucas’ 1977 film, Star Wars: A New Hope, Luke Skywalker is introduced as a young farm kid with big dreams and nowhere to go.

The beginning of causality is when Obi-Wan Kenobi invites him to go to Alderaan and learn the ways of the Force.

Luke rejects Obi-Wan’s invitation initially, but once the Empire murders Luke’s relatives and destroys his home, he accepts Obi-Wan’s offer, and the adventure has begun.

Jurassic Park

In Steven Spielberg’s 1993 film, Jurassic Park, we meet Dr. Grant on his dig. He’s busy unearthing fossilized Velociraptors.

Then billionaire John Hammond invites Dr. Grant and his colleague, Dr. Sattler, to come visit his dinosaur park and give it an “expert review.”

Grant is initially hesitant, but Hammond offers to fund Grant’s dig. This is an opportunity the paleontologist cannot give up. Grant and Sattler agree, and the story is off to the races.

Middle: change of plans

As the protagonist pursues her plan, she meets growing resistance until something happens that makes further progress impossible. This forces her to search for, find, and commit to a new trajectory.

This may or may not cause the protagonist’s goal to change, but it always disrupts her plan for how to reach the goal. She must find a new way.

Progress

During the progress phase of the story, the protagonist’s plan starts off reasonable but conservative. She wants success with the minimum effort necessary.

The story won’t let her get it so easily. She meets growing resistance. Her plan becomes less and less tenable, and she must make larger and larger adjustments to keep things on track.

Star Wars: A New Hope

Obi-Wan takes Luke to Mos Eisley spaceport to book passage to Alderaan. There are Imperial stormtroopers everywhere, searching for them and their droids. To avoid official notice, they must go to the black market.

In a seedy cantina, Luke is accosted by a thug. Obi-Wan must step in to protect him. Luke is out of his element.

Then, just as they’re about to board their transport, the stormtroopers catch up with them. Their transport launches in a shower of gunfire. They barely make it off the planet.

As they travel, Obi-Wan starts to train Luke to sense the Force. But the smuggler captain of their transport openly derides their beliefs.

Jurassic Park

The scientists arrive at the park. They’re uncertain of what to expect but ready to humor Hammond in return for his increased funding.

Then they see real, living dinosaurs. They’re suprised and awed. There’s a sense of delight and wonder . . . and, as things continue, a subtle but growing undercurrent of danger.

Resistance becomes explicit as they meet over lunch to discuss the implications of Hammond’s new technology. The overall sentiment is, “Are we sure we know what we’re getting into?”

Dr. Ian Malcolm, another of the visiting experts, voices criticism:

“The lack of humility before nature that has been displayed here staggers me. . . . Your scientists were so preoccupied with whether or not they could that they didn’t stop to think if they should.” (Koepp, Pages 37-38)

After lunch, they begin the tour. The challenges increase:

- Grant (who dislikes children) narrowly avoids getting stuck with Hammond’s grandkids.

- The dinosaurs refuse to show up when the cars drive by.

- A tropical storm threatens to cut the tour short.

- And (unbeknownst to the protagonists) Dennis Nedry, the park’s IT system administrator, is planning to betray Hammond. He’s going to shut down park security so he can steal dinosaur embryos to sell to a competitor.

Eventually, the storm becomes so threatening that Hammond must call a premature stop to the tour. Disappointed, the scientists turn around and start heading back.

Disaster

At the disaster, something happens that makes it impossible for the protagonist to continue in her current plan. In an Event story, this is an action or revelation that comes from the external world.

The disaster may cause the protagonist to change her goal, as in our two examples, but that’s not always the case.

Star Wars: A New Hope

Luke and Obi-Wan arrive in the Alderaan system to find that the Empire has destroyed the planet. Their original goal of taking the droids to that safe haven is now impossible.

They must flee. But before they can escape, the’re discovered by an Imperial fighter craft. Han Solo, the captain of their transport, decides to pursue and destroy the fighter. He wants to eliminate the witness so that they can avoid being tracked.

But they soon realize this was a mistake. Pursuing the fighter, they run across the Empire’s Death Star battle station, lurking in the system. By the time they recognize what’s happening, they’re already caught by the Imperials’ tractor beam. They’re trapped and taken aboard.

Jurassic Park

Nedry locks the computer system so that nobody else can control it. On his way out of the park, he stumbles upon a carnivorous dinosaur and is killed.

At the park’s control room, Hammond, Sattler, and a couple of others watch with confusion as the park’s security system, which keeps the dinosaurs in their enclosures, starts to shut off. They try to get security back online, but they cannot get past Nedry’s password lock.

Out in the park, Grant, Malcolm, Genarro (the park’s lawyer) and the kids are riding past the Tyrannosaurus paddock when the power shuts off. The cars, which are run by the park’s control system, stop and go dark.

Moments later, the T-rex approaches. They watch in horror as it slices through the now non-electrified fence and steps out into the roadway with them.

Genarro tries to escape on foot. The T-rex catches and eats him. Then, the massive predator turns its attention back to the cars.

It approaches the one in which the kids are hiding . . .

The Ordeal

“Dreams and wishes must be tested in the crucible of reality, in action, by doing.”

— Christopher Vogler (Vogler, Page 379)

In the wake of the disaster, the plan is in shambles, and protagonist must confront an uncomfortable realization: to achieve success, much more will be asked of her than she at first thought.

- Luke Skywalker cannot just follow his mentor to Alderaan. He must face Vader in combat above the Death Star.

- Dr. Grant cannot just ride through the park and hand in his evaluation. He must struggle to survive, crossing the park on foot — all while caring for (relatively) helpless children.

The Ordeal is a phase of significant opposition. It’s similar to the Dilemma in a Character story. But where in a Character story, the challenge is all about the choices of the protagonist, in an Event story, this phase is a challenge to the protagonist’s abilities.

It’s a sort of “gauntlet” that must be run; (Truby, Page 299) a long, escalating series of trials; a test of the protagonist’s mettle. The image that springs to mind is the intense heat of a refinery, where metals are purified and the slag burned away.

The function of the Ordeal is to prove that the protagonist has earned the right to the story’s ending. Without struggle, we don’t respect achievement. So if Event stories are about achievement, the most straightforward way to make the ending satisfying is through struggle. The protagonist can only win by displaying courage and persistence in the face of great opposition.

If the emotional payoff in an Event story is the thrill of adventure and success, the Ordeal counters that with its opposite: Fear and doubt rear their ugly heads. The protagonist realizes that perhaps the outward goal may not be achieved at all. And — more than that — even what little of value she had at the beginning (or has obtained along the way) may be taken from her.

She may lose everything.

“Near the end of the story, the conflict between hero and opponent intensifies to such a degree that the pressure on the hero becomes almost unbearable. He has fewer and fewer options, and often the space through which he passes literally becomes narrower. Finally, he must pass through a narrow gate or travel down a long gauntlet . . . This is also the moment when the hero visits ‘death.’”

— John Truby (Truby, Page 299)

The Ordeal takes the protagonist to a place where the problem she faces feels truly insurmountable. No amount of effort will overcome it.

Star Wars: A New Hope

| Character action | Escalation |

|---|---|

| Hide while Obi-Wan disables the tractor beam | Discover that Princess Leia is aboard and scheduled for execution |

| Rescue princess | End up trapped in the garbage masher |

| Escape garbage masher | Chased by stormtroopers |

| Escape stormtroopers and get back to transport | Obi-Wan is killed |

| Escape Death Star | Chased by Imperial TIE fighters |

| Escape TIE fighters and get to rebel base | Death Star follows them to the rebel base |

| Attack Death Star | One by one, Vader shoots down the rebel fighters |

| Luke begins his attack run | Vader positions himself to shoot Luke down |

Jurassic Park

| Character action | Escalation |

|---|---|

| Escape T-rex | Must cross park on foot |

| Successfully cross park | Must climb over electric fence |

| Go to bunker and restore power to the park | Chased by Velociraptors |

| Climb over fence | Timmy electrocuted |

| Timmy resuscitated and return to park center | Trapped in the kitchen by Velociraptors |

| Escape Velociraptors in kitchen and get to control room, fix system | Velociraptors get into control room |

| Escape to atrium | Velociraptors follow and corner them |

A way forward

If you’ve truly placed your protagonist in a position in which no amount of her own effort will resolve her dilemma, something external must come to effect a rescue. You could think of this as what J. R. R. Tolkien called a “eucatastrophe.” An ally, long forgotten, appears at the right moment to help. Or, the protagonist suddenly realizes something, which was set up earlier in the story, and which now becomes the key to pushing through.

This moment maps to the epiphany in an idea story or the decision in a character story.

The rescue doesn’t always have to be something external to the protagonist. In Jonathan Demme’s 1991 film adaptation of Thomas Harris’ The Silence of the Lambs, Clarice Starling is trapped in the basement with the killer. But she’s a great shot. When she hears the click of the killer’s gun behind her in the darkness, she turns and shoots him.

Regardless of whether the breakthrough is supplied from outside the protagonist or from her own actions, it needs to be properly motivated. Otherwise, it feels unsatisfying.

Star Wars: A New Hope

In Star Wars: A New Hope, Han Solo suddenly appears, flying with the sun at his back. He shoots off the fighters pursuing Luke, clearing Luke’s way.

Jurassic Park

In Jurassic Park, the T-Rex appears, seemingly out of nowhere. It attacks the Velociraptors, creating a diversion. Dr. Grant, Dr. Sattler, and the kids flee while the dinosaurs are distracted.

End: goal achieved

In the climactic moment of an Event story, the goal which the protagonist set out to pursue is either achieved or not achieved. Then, the resulting implications for the protagonist’s situation are explored in the resolution.

Star Wars: A New Hope

Trusting the Force, Luke shoots a proton torpedo down the Death Star’s exhaust vent. This triggers a chain reaction that destroys the battle station.

Luke and his new friends are honored as heros. The young farm kid has achieved his big dreams, though the reality was different than he imagined.

Jurassic Park

In Jurassic Park, the rescue and climactic moment are telescoped into one another in the scene when the T-Rex appears. After this, Dr. Grant, Dr. Sattler, and the kids hop into a waiting car driven by Hammond and Dr. Malcolm. They escape from the park.

As they ride away on a helicopter, we see Dr. Sattler and Dr. Grant share a brief moment of connection. They’ve done it. After all the chaos, they’re safe and at peace.

Rate this note

Read this next

The realm of appropriate payoffs

The best story payoffs match the setup while being better than expected.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.