Beginning, middle, and end part 6: Character stories part 2

Summary: The key change in a character story is about worldview and beliefs. The dilemma and decision show how the protagonist grapples with change, and the ending demonstrates that her change was genuine.

“To carry an emotional appeal to an audience, a story must not only show the results of a method of problem solving, but must document the appropriateness of each step as well.”

— Melanie Anne Phillips (Phillips, Location 1052) (Emphasis mine)

Recap

This note is a part of a series.

- Aristotle misinterpreted

- In search of a useful framework

- Story types

- Idea stories

- Character stories part 1

- Character stories part 2

- Event stories

This is the second of two parts on character stories. See the first part here.

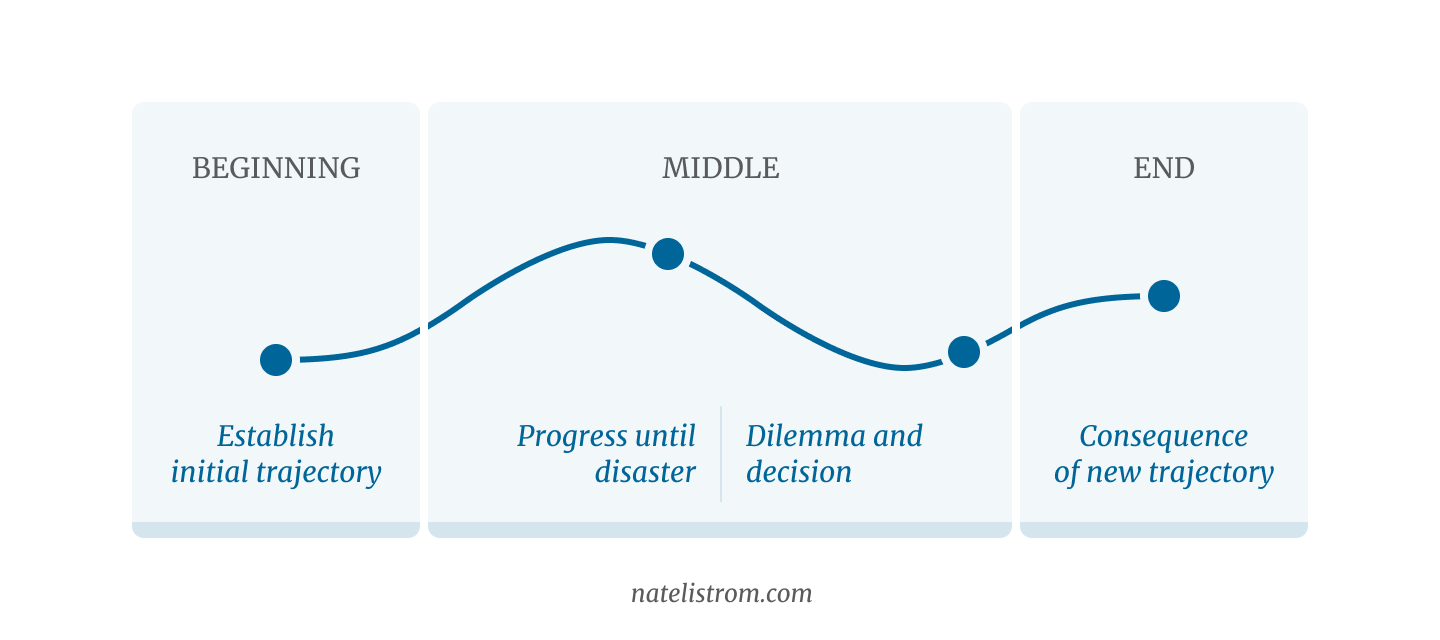

As a reminder, we’re trying to develop a useful structural framework based on Aristotle’s “beginning, middle, and end.” Aristotle’s definitions give us clarity for the beginning and end, and we’re using Dwight Swain’s scene-sequel format to fill in the middle.

Here’s what our framework looks like:

| Beginning |

|

|---|---|

| Middle |

|

| End |

|

We pick up with the third step in the middle of a character story, the “period of grappling with the implications of the disaster and searching for a new way forward.”

Dilemma

Change always has a cost. In order to embrace a new way of being, you have to give something up. There’s a looming specter of the death of the old way. Snyder calls this phase the “dark night of the soul.” (Snyder, Page 88)

In character stories, the purpose of the dilemma is to force the protagonist to evaluate all possible ways of preserving herself without changing and discover that nothing will do. (Phillips, Location 883) The story must illustrate that, to succeed, the protagonist cannot do anything but change. It is the only way.

This results in a period of reaction, grief, and deliberation. Is the risk of giving up the familiar worth the potential gain?

“The clock is ticking, options are running out. If the Main Character doesn’t choose one way or the other, then failure is certain. But which way to go? There’s no clear-cut answer from the Main Character’s perspective.” (Phillips, Location 885)

Pride and Prejudice

In Pride and Prejudice, the dilemma manifests itself chiefly as Elizabeth realizes — after Wickham and Lydia elope — that her feelings for Darcy have changed:

“Never had she so honestly felt that she could have loved him, as now, when all love must be vain.” (Austen, Page 242)

She has not yet realized the error of her judgments, but she knows that something has shifted in her heart. Over the next few chapters, as the external events play out, Elizabeth will grapple with the implications of that change.

Jurassic Park

Dr. Grant’s dilemma manifests mostly through his relationship to the children he’s now responsible for protecting. Unsurprisingly, he’s not very good at it, playing a role he’s never before inhabited.

Lex’s GASPS are getting louder. She’s terrified.

GRANT

“Hey, come on, don’t – don’t – don’t – just – just –”He touches her, but it’s awfully awkward, more of a pat on the head than anything strong or reassured. (Koepp, Page 82)

Moments later:

GRANT (cont’d)

“Come on out, Lex. Hiding isn’t a rational solution; we have to improve our situation.” (Koepp, Page 85)

Of course, asking a terrified child to seek a “rational solution” isn’t an effective approach. How will Grant connect with these kids so that he can help them? He must adapt.

It’s a metaphor for the broader dilemma he’s facing: How will he deal with the fact that his world is changing, and he doesn’t have control over it?

Decision

In character stories, more than idea or event stories, the key moment that solidifies the rest of the plot must come from within the protagonist. Facing the dilemma, she makes a decision and commits herself to a new way of being.

Shapes of change

Sometimes, similar to the “epiphany” in an idea story, the moment of decision can be quite distinct. Pressures gradually build up over the course of the story and then, like the slipping of techtonic plates, the protagonist makes a sudden turn. Dramatica creator Melanie Anne Phillips calls this a “leap of faith.” (Phillips, Location 883) The strong contrast of a moment like this makes it easy for audiences to see.

Change in other stories might be more continuous and happen by degrees.

“The Main Character gradually shifts his perspective until, by the end of the story, he has already adopted the alternative paradigm with little or no fanfare.” (Phillips, Location 899)

There is still a final moment when the course of the story is settled and we know that the protagonist has changed, but it’s much less prominent, more felt than seen.

Types of change

There are also a number of different types of decision.

-

First comes what author K. M. Weiland calls the “positive change arc,” this type of decision is all about the protagonist heroically committing to abandon her old self and take up a new way of being. (Weiland, Page 8)

-

Second is the decision in a tragedy — a “negative change arc.” This type of decision is all about the protagonist knowingly doubling down on her old, failed way of being. (Weiland, Page 9)

-

Third comes a variant of the character story in which it is the society around the protagonist, rather than the protagonist herself, which changes. Weiland calls these “flat arcs.” (Weiland, Page 8)

Standing firm

Vogler calls protagonists in flat arcs “catalyst characters,” focusing on the effect that they have on others. (Vogler, Page 40)

Phillips explores a similar theme but with a different perspective, calling them “steadfast characters.” To her, even characters that hold onto their worldview can still change in subtle ways, often deepening their resolve.

“Steadfast Main Characters will not add nor delete a characteristic, but will grow either by holding on against something bad, waiting for it to Stop, or by holding out until something good can Start.” (Phillips, Location 2273)

Both the key decision in a negative arc — in which the protagonist stubbornly maintains her her lie — and a flat arc — in which the protagonist stubbornly maintains the truth and causes others to abandon their lies — can be thought of as “steadfast character” decisions.

Pride and Prejudice

In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth’s perspective toward Mr. Darcy shifts slowly over the entire second half of the story.

- At the midpoint, she actively despises him for hurting Jane.

- When she visits Pemberley and observes him with her uncle and aunt, she begins to soften to him. She’s confused. His behavior challenges the previous judgments she made about him.

- After Lydia elopes with Wickham and Darcy is removed from her life, Elizabeth begins to see that he could have meant more to her.

The function of all this is to demonstrate to Elizabeth that her hasty judgment was wrong. That realization comes slowly.

Nevertheless, there is still a distinct moment when Austen makes it clear that Elizabeth has changed. It’s represented by an explicit reversal in her judgment of him:

“The proposals which she had proudly spurned only four months ago, would now have been most gladly and gratefully received! . . . She began now to comprehend that he was exactly the man who, in disposition and talents, would most suit her . . . . by her ease and liveliness, his mind might have been softened, his manners improved; and from his judgement, information, and knowledge of the world, she must have received benefit of greater importance.” (Austen, Page 271) (Emphasis mine.)

Jurassic Park

In Jurassic Park, Dr. Grant’s moment of decision is also quite distinct. It happens when he and the children spend the night together in a tree, hiding from the Tyrannosaurus rex.

At the beginning of the story, Grant was portrayed as future-averse. He disliked children — to the point of using a petrified raptor claw to antagonize one. The raptor claw has become a symbol of Grant’s old identity.

Now, in the tree, Grant finds himself sharing a moment of connection with kids. He’s almost a father figure to them. The contrast in his relationship with children hints at deeper changes.

Things get philosophical. One of the kids asks Grant, “What are you and [Dr. Sattler] gonna do now if you don’t have to dig up dinosaur bones any more?” (Koepp, Page 92)

It’s a good question. His former profession is irrelevant now that real, live dinosaurs are walking around. Grant can no longer run from the future.

“I guess I’ll just have to evolve.” (Koepp, Page 92)

He casts aside the fossilized raptor claw. He embraces change.

End: Living the new belief

A promise is only good if you see it through. The purpose of the final section of a character story is to test and prove the commitment the protagonist made. It demonstrates how the results of the protagonist’s decision play out.

Generally, this means a climactic moment and a resolution.

- In the climactic moment, the protagonist faces some kind of challenge. (Swain, Page 193) Instead of responding in the old way, she responds in the new way. Her actions embody who she is now. (Coyne, Page 185) She passes the test.

- Then in the story’s resolution phase, the consequences of the change (for the protagonist and her world) play out. Having proven her change through action, she settles into a new equilibrium. (Truby, Page 50) The end of the story demonstrates this “after image.” It contrasts with the “before image” from the beginning, showing how life is different on this side of the change. (Snyder, Page 90)

Not every character story resolves in a perfect happy ending or a perfect tragedy. For example, Kenneth Lonergan’s 2016 film, Manchester by the Sea has a mixed, bittersweet ending. Still grappling with his pain, protagonist Lee Chandler cannot take his nephew to live with him. But he commits to being a part of his life. This demonstrates that Lee can change, but that he has not yet reached wholeness.

Pride and Prejudice

Pride and Prejudice is interesting in that the proof of character change and the emotional climactic moment of the romance plotline come in different scenes.

Through the dilemma phase, Elizabeth has realized that she does, indeed, have deep regard for Mr. Darcy — the kind of regard for which she’s always hoped. She mis-judged him, and she repents of her judgment. But her repentance must be put to the test.

The proof comes in Chapter 56. The esteemed (though unpleasant) Lady Catherine de Bourgh visits Elizabeth. Lady Catherine has heard a rumor that Mr. Darcy has designs on Elizabeth. She intends for Mr. Darcy to marry her daughter, so he has come to obtain Elizabeth’s promise not to marry Mr. Darcy.

But, of course, Elizabeth rejects the request.

Having once promised never to accept Mr. Darcy (if he asked her to dance), Elizabeth now promises never to reject him (if he asks her to marry). She has completely reversed positions.

The emotional climactic moment comes a couple of chapters later. Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy happen to be walking together, semi-privately. Elizabeth seizes the moment. She thanks Mr. Darcy warmly for his help to her family in the matter of Lydia’s elopement. Sensing that her attitude toward him has changed, Mr. Darcy responds:

“‘If you will thank me,’ he replied, ‘let it be for yourself alone. That the wish of giving happiness to you might add force to the other inducements which led me on, I shall not attempt to deny. But your family owe me nothing. Much as I respect them, I believe I thought only of you.’

“Elizabeth was too much embarrassed to say a word. After a short pause, her companion added, ‘You are too generous to trifle with me. If your feelings are still what they were last April, tell me so at once. My affections and wishes are unchanged, but one word from you will silence me on this subject for ever [sic].’” (Austen, Page 315) (Emphasis original.)

He proposes. She accepts.

The chapters that follow depict the results. Her family is incredulous, knowing her earlier dislike of him. Austen contrasts Elizabeth’s marriage to Mr. Darcy and the other couples in the story, including Lydia and Mr. Wickham. We learn how Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy settle into their new bliss.

Jurassic Park

In David Koepp’s screenplay for Jurassic Park, the main movement Dr. Grant’s character change resolves about three quarters of the way through the story.

When Dr. Grant casts aside the raptor claw, the action serves both to show his decision and also prove his commitment to it. The two functions are condensed into a single beat. Thus, the decision and the climactic moment of his character arc happen at the same time.

During the rest of the story, Dr. Grant lives in his new equilibrium, acting as a protector and guide for the children. (You could argue that there are later character moments of significance, like when one of the children is electrocuted, and Dr. Grant has to resuscitate him. But to me, it seems those are more properly identified as beats of the event story, rather than the character arc.)

In the final scene of the film, we see a “closing image” of Dr. Grant in sharp contrast to how he began. At the start, he was digging up petrified proto-bird fossils from the solid earth. Now, he’s seen riding a helicopter, watching modern birds fly over the ever-changing waters of the sea. At the start, he disliked children. Now, he’s got one on each shoulder.

He’s learned to evolve.

Rate this note

Read this next

Beginning, middle, and end part 7: Event stories

The key change in an event story about the protagonist's situation and circumstances. The beginning introduces an outward goal, the middle shows the struggle to obtain it, and the ending shows success or failure.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.