Beginning, middle, and end part 2: In search of a useful framework

Summary: Beginning, middle, and end can be framed as the cause of change, the process of change, and the consequence of change. Scene-sequel format helps illustrate the process of change.

Previously, we looked at how I’d misunderstood Aristotle. I’d interpreted his “beginning, middle, and end” as structural terms that merely defined themselves — obvious and unhelpful.

But it turns out Aristotle wasn’t primarily concerned with structure. His point was that a story should be complete and uncontaminated. It should contain every necessary part of itself and nothing else.

Granted that structure wasn’t his focus, in this note we’ll explore what Aristotle’s formula does and doesn’t say about story structure.

This note is a part of a series.

- Aristotle misinterpreted

- In search of a useful framework

- Story types

- Idea stories

- Character stories part 1

- Character stories part 2

- Event stories

A puzzle with a piece missing

There’s an irony here. Although Aristotle wasn’t concerned with structure per se, his prescriptions about wholeness can lend us some structural insight.

Let’s unpack this a little.

Beginnings and endings

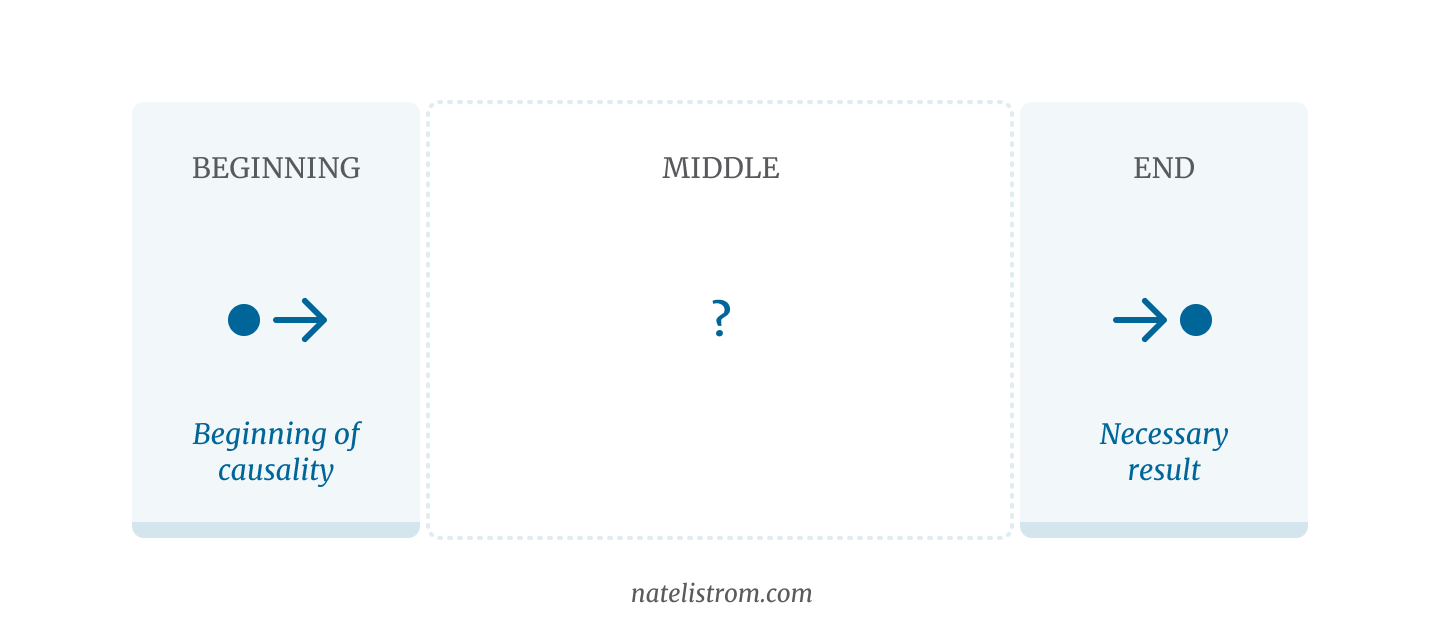

Aristotle said that the beginning of a story is “that which does not itself follow anything by causal necessity, but after which something naturally is or comes to be.” (Aristotle, Part VII) In other words, a story begins with the first domino to fall, the thing that causes everything else.

The end is “that which itself naturally follows some other thing, either by necessity, or as a rule, but has nothing following it.” (Aristotle, Part VII) The end is whatever final consequence inevitably results from the story’s events.

Although terse, these definitions are useful for story structure. They give us a measuring rod for what a beginning and ending should be.

Mind the gap

Unfortunately, Aristotle’s description of the middle isn’t quite as helpful. “A middle is that which follows something as some other thing follows it.” (Aristotle, Part VII)

This just says that whatever is in the middle is caused by the beginning and, itself, causes the end. But it doesn’t say what, specifically, it should be.

So, there’s a gap. To fill it, we’ll need to import ideas from somewhere else.

Fill in the blank

To figure out how to structure a middle, let’s first ask a different question: What should go in the middle of a story?

There are a lot of great answers, of course. For the sake of today’s exploration, let’s look to seasoned book editor Shawn Coyne, who founded the Story Grid methodology. Coyne claims that “change is the substance of Story.” (Coyne) On some deep level, stories are about change.

Thus, if we ask what goes in the middle of a story, one answer is: change.

So now we’ve made a little progress. We have something that looks like this:

- Beginning: The thing that causes everything else

- Middle: Some kind of change

- End: The inevitable consequences

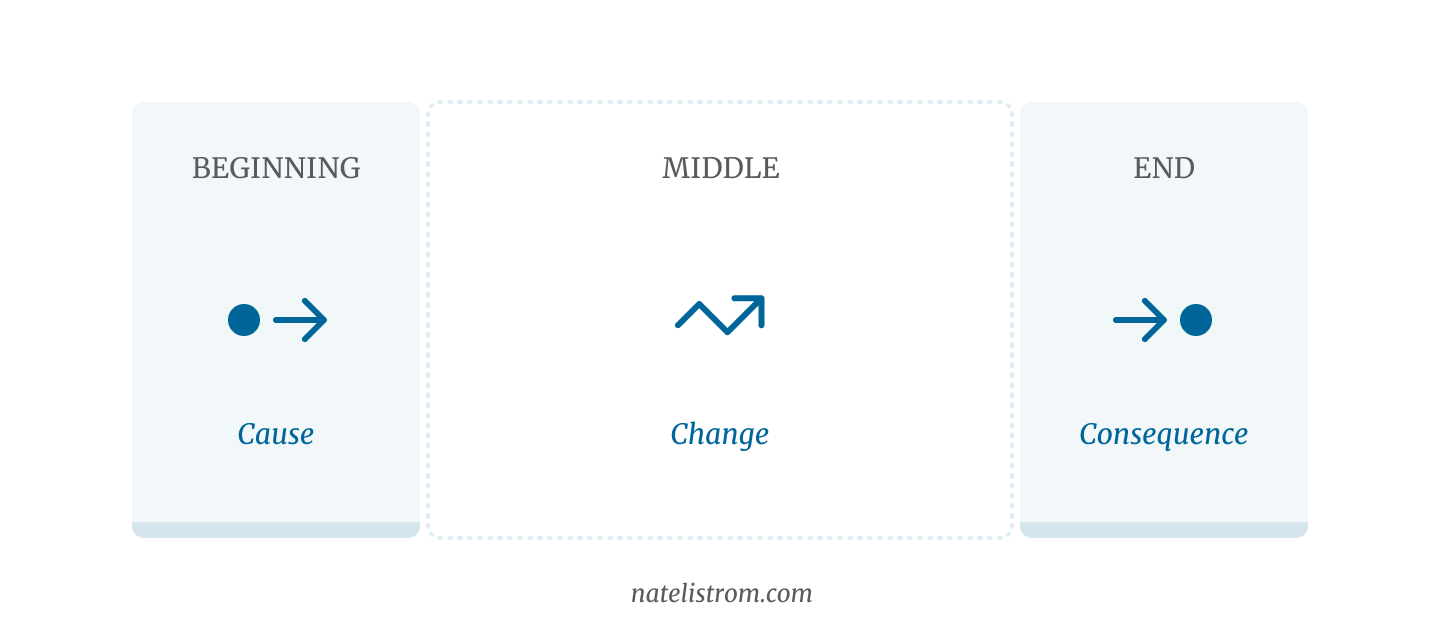

We might re-frame that as:

- Beginning: The thing that causes change

- Middle: The process of change

- End: The consequence of change

That’s a bit more promising. We have a direction for the middle, now: It’s the process of change.

The next task is to see if we can discover how to structure the process of change.

How humans process change

I’m sympathetic to the theory that the archetypal patterns in stories follow human psychology. They arc based on how our minds naturally process information. A Coyne seems to agree. He explains the process of dealing with change in terms of Kubler-Ross’s five stages of grief. (Coyne)

Kubler-Ross is insightful, but her model isn’t quite as easy to use in storytelling as I’d like. Trying to blindly shoehorn in a “bargaining” phase, for example, feels a bit like George Lucas’ injecting a virgin birth into Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (supposedly because Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey suggested it). It can work. But, if you don’t understand what underlying function it’s supposed to be performing, it may feel forced.

We need a straightforward model — a tool we can easily grab and use when either building a story or analyzing one we’ve just completed.

And in fact, such a tool exists.

Scene-sequel format gives shape to change

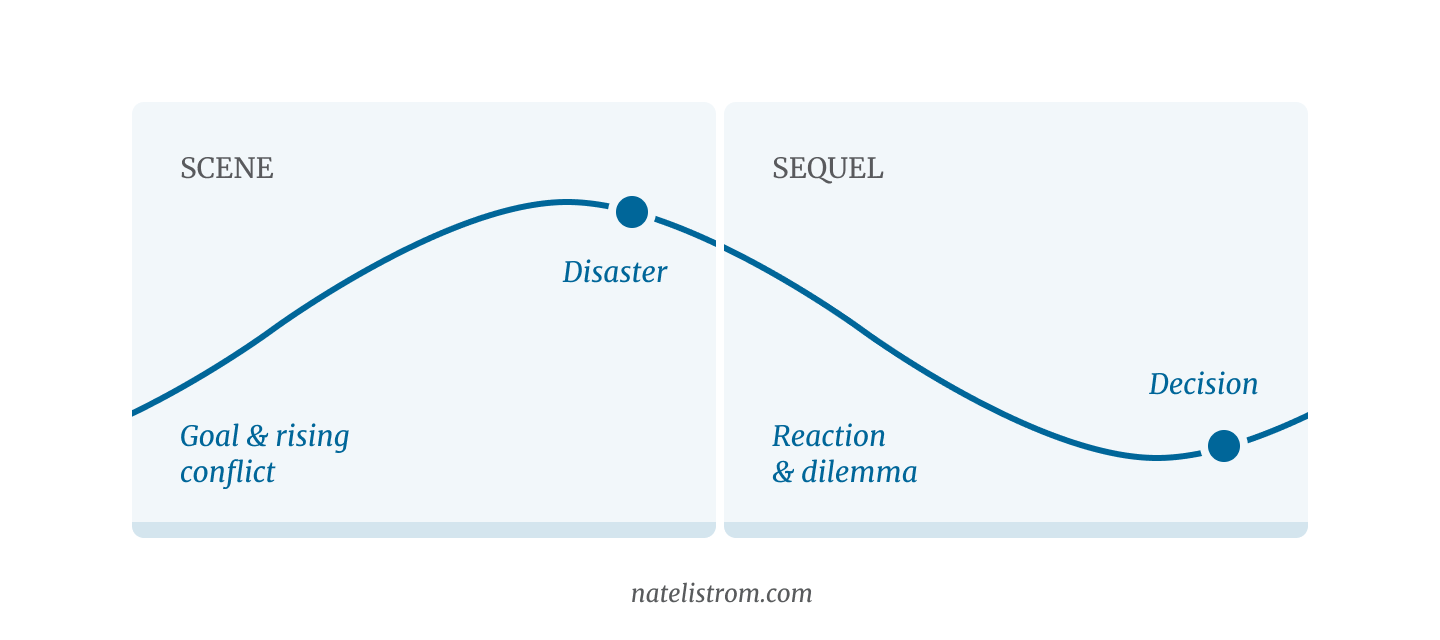

I’ve written before about Dwight Swain’s scene-sequel format. Swain’s original formula is a six-stage model, (Swain, Pages 85-100) but it distills nicely into four. It’s a handy map of the general arc of a change.

Here’s what it looks like:

- Goal and plan: The story is moving in a particular direction. The protagonist makes progress but faces increasing resistance.

- Disaster: Something happens that makes it impossible to continue with the current trajectory.

- Reaction and dilemma: The plan is in shambles. The goal seems unreachable. The protagonist must grapple with an uncomfortable truth: in order to continue forward, something must change. She must weigh her options and consider the trade-offs.

- Decision: A new direction is established. B The process of change is complete.

So, what do you need to structure the process of change?

- A trajectory

- A disaster that makes it impossible to continue in that trajectory

- A period of grappling with the implications of the disaster and searching for a new way forward

- The establishment of a new trajectory

(If you’re looking closely, you’ll notice that this is essentially two units of the trajectory and payoff framework. The disaster creates the payoff of the first unit, and the decision creates the payoff of the second.)

Putting it all together

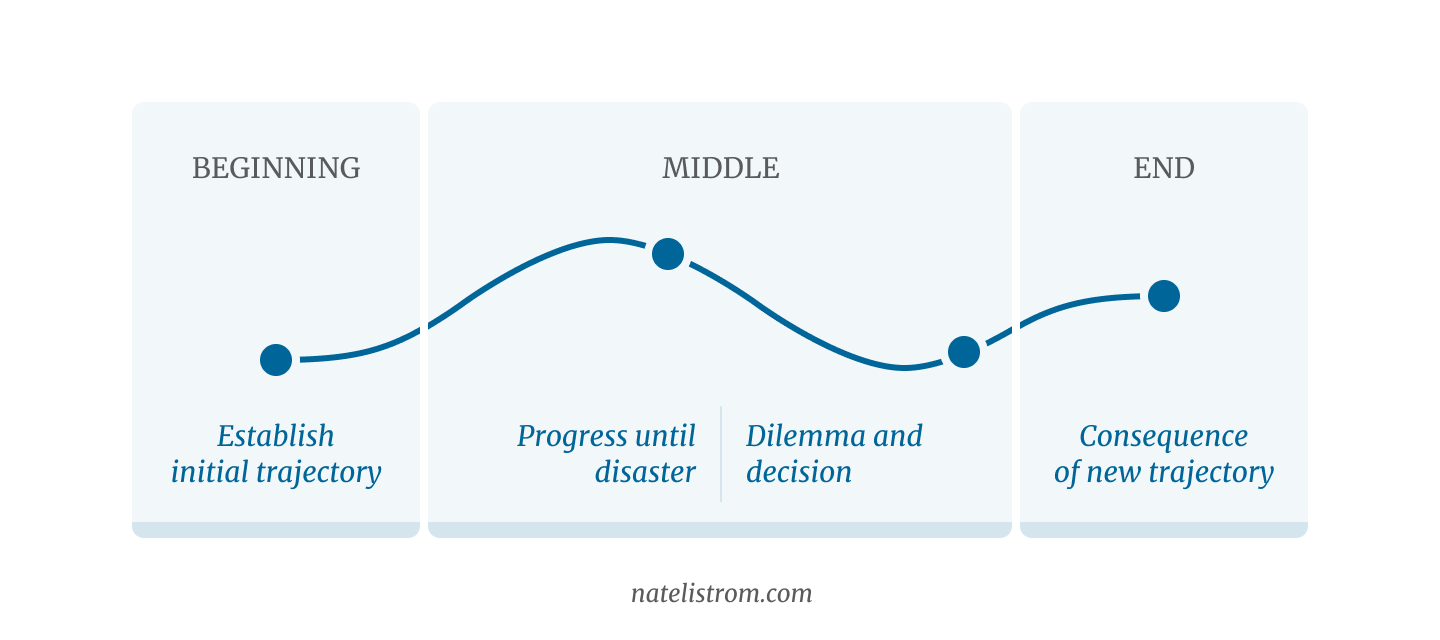

Now that we have a basic framework for the process of change in-hand, let’s join it to our definitions of beginning and end.

Here’s what it looks like:

Beginning

- Something happens, which establishes a trajectory

Middle

- That trajectory is pursued with growing resistance until . . .

- A disaser happens, which makes it impossible to continue in that trajectory

- There’s a period of grappling with the implications of the disaster and searching for a new way forward

- A new trajectory is established

End

- The consequences of the new trajectory play out

Different story resolutions

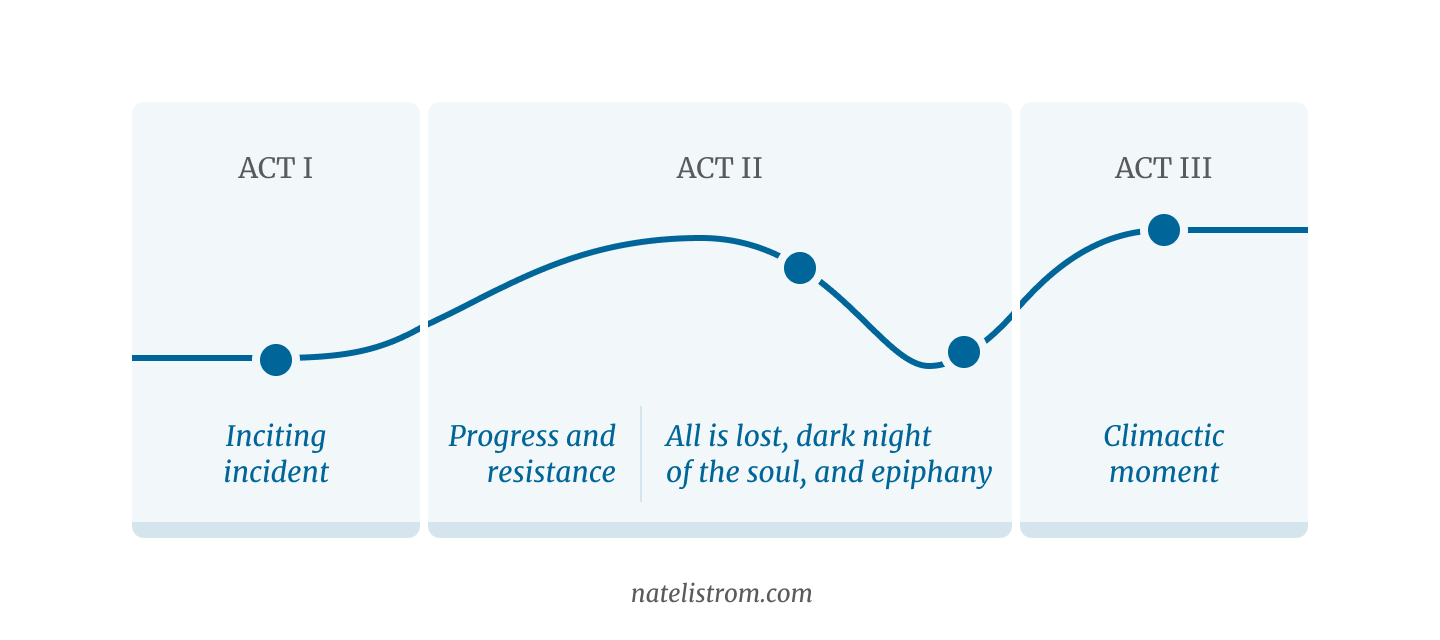

This framework applies quite nicely to a whole story. In fact, if you subscribe to popular screenwriting structures, you can see that beginning, middle, and end map to the three acts. C

For longer stories, there can be multiple steps of change in the middle. The steepest swings and most significant moment of change tend to be compressed toward the end to maximize emotional impact.

Act I

- The inciting incident can be the “something that happens, which establishes a trajectory.”

Act II

- The first half of the second act can be the “trajectory pursued with growing resistance.”

- The “disaster that makes it impossible to continue in the trajectory” can lead to what screenwriting consultant Blake Snyder calls the “all is lost” moment and “dark night of the soul.” (Snyder, Pages 86-88) It’s the phase in which the protagonist faces her “period of grappling with the implications of the disaster and searching for a new way forward.”

Act III

- And, once she’s found it, the climax can be the “consequence of the new trajectory playing out.”

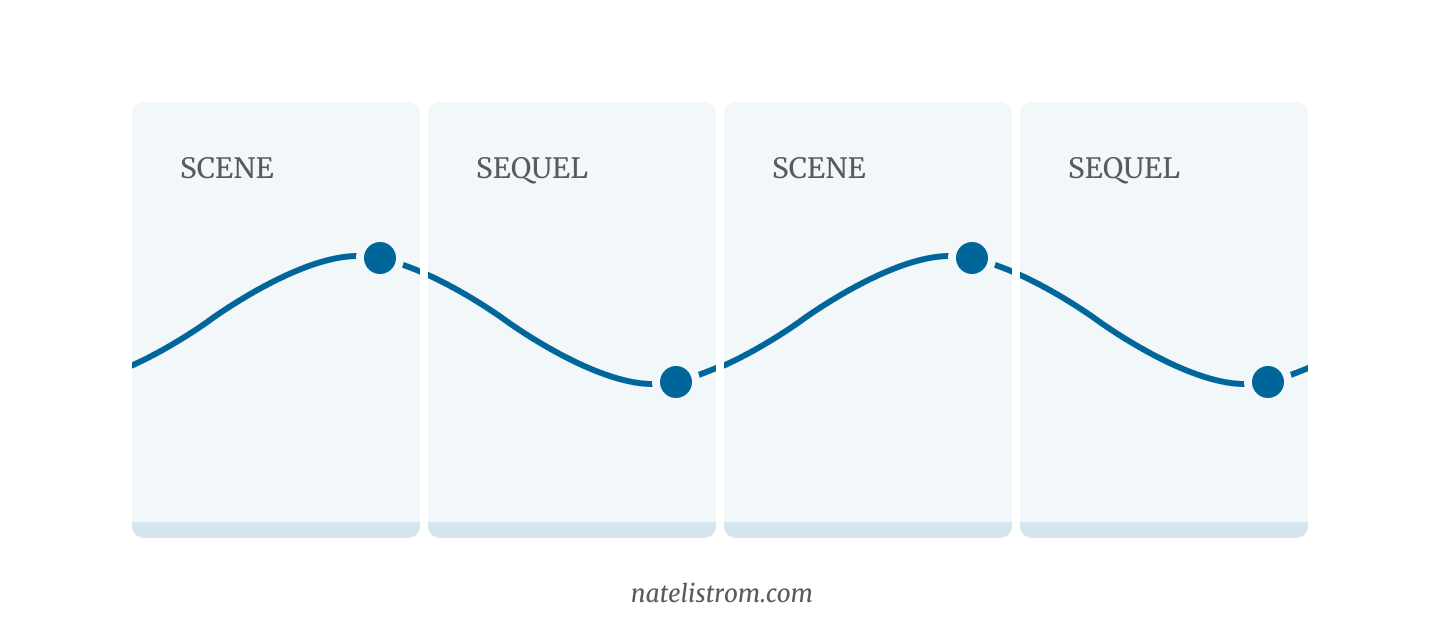

Individual scenes

You can also apply the framework to individual scenes. The difference is that, unless you’re beginning or ending an arc, scenes just contain the middle part. The “new trajectory that’s established” in one scene becomes the “trajectory that’s pursued with growing resistance” in the next.

Opening and closing images

One last technical note.

While the inciting incident can be thought of as the “beginning of causality” and the climactic moment as the “necessary result,” most stories have additional material before and after.

- Before the inciting incident, there’s often a period of time when audiences get to know the protagonist in her everyday life.

- After the climactic moment, there’s often a period of resolution where we see the new state of her life.

Snyder calls these the “opening image” and “final image.” (Snyder, Page 90)

The core cause-process-consequence arc of change doesn’t seem to include these sections. If Aristotle is correct about only including what’s necessary, why are they here?

I think the answer comes down to theme.

Consider the following example:

| Before | Change | After |

|---|---|---|

| I needed money, so I… | …learned to ride a bike… | …and now I earn money doing a paper route. |

| I was lonely, so I… | …learned to ride a bike… | …and now I ride to the park and hang out with friends. |

In both cases, the change in the middle is the same — learning to ride a bike. But the purpose of the change is different. We bracket the change with “snapshots” of the world in different states in order to clarify what the change was all about. The comparison creates meaning.

In this way, I think you could argue that these extra bits are necessary. They’re not within the inner chain of causality, true. Instead, they provide essential framing that helps us properly understand it.

Snyder himself seems to hint at this:

The opening image is . . . an opportunity to give us the starting point of the hero. It gives us a moment to see a ‘before’ snapshot . . . There will also be an ‘after’ snapshot to show how things have changed . . . Because a good screenplay is about change, these two scenes are a way to make clear how that change takes place.” (Snyder, Page 72) (Emphasis mine)

Not done (quite) yet . . .

Frameworks are fine in the abstract. But, as they say, “the proof of the pudding is in the eating.” We still need to test out our theory to see if it holds up. We’ll look at that — and the insights that come from it — soon.

Onward . . .

Rate this note

Read this next

Beginning, middle, and end part 3: Story types

The three key types of change in stories are revelation, character decision, and external action. These map to idea, character, and event stories in Orson Scott Card's MICE quotient.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.