Beginning, middle, and end part 4: Idea stories

Summary: The key change in an idea story is about understanding. The beginning introduces a question, the middle shows the pursuit of an answer, and the ending reveals it.

“Drama cannot exist without change; arguably it is change, so in a world where detectives stay constantly the same, what fuels the dramatic engine? In a classic episode of Columbo or Inspector Morse, the protagonist seeks the ‘truth’ that lies behind the crime they’re investigating . . . Rather than a flaw, these characters have a deficiency of knowledge.”

— John Yorke (Yorke, Location 1339) (Emphasis mine)

Idea stories revolve around a central question, which the audience wants answered. (Kowal) Common forms of idea stories include mysteries, police procedurals, and some “high concept” science fiction and fantasy stories.

- The key change in an idea story is about knowledge or understanding.

- The emotional fulfillment audiences derive from these types of stories is the thrill of discovery, a feeling of epiphany.

- The key turning points in idea stories are revelations.

Recap

This note is a part of a series.

- Aristotle misinterpreted

- In search of a useful framework

- Story types

- Idea stories

- Character stories part 1

- Character stories part 2

- Event stories

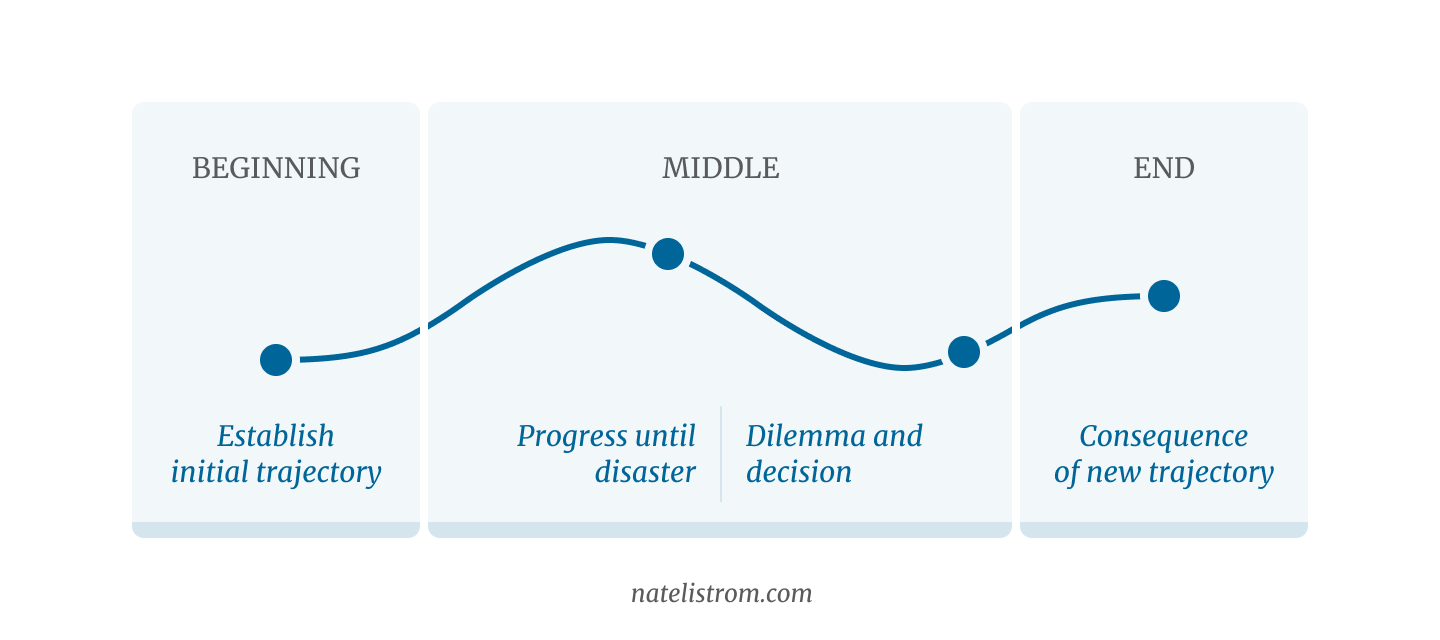

As a reminder, we’re trying to develop a useful structural framework based on Aristotle’s “beginning, middle, and end.” Aristotle’s definitions give us clarity for the beginning and end, and we’re using Dwight Swain’s scene-sequel format to fill in the middle.

Here’s what that looks like:

| Beginning |

|

|---|---|

| Middle |

|

| End |

|

So the question is, how does this fit an idea story?

Beginning: raising a question

In an idea story, the “something that happens, which establishes a trajectory” is about raising a key question that the audience and — most often — the protagonist wants answered. (There are some stories in which the protagonist is at first reluctant to investigate.)

Pure idea stories don’t require much establishing setup. They can successfully open on a scene, like the discovery of a body or the arrival of aliens, which introduces the central question. This differentiates them from character and event stories, which generally hinge much more tightly on the introduction of the protagonist and her call to adventure.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

In J. K. Rowling’s 1998 fantasy novel Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, the beginning of causality is when Dobby the house elf appears in Harry’s room and attempts to stop him from going to Hogwarts. This raises the question, “What motivated Dobby to do this?” and, “What’s the danger that Dobby claims Harry should avoid?” This thread later develops into the key question that drives much of the plot: “Who is the heir of Slytherin?”

Rendezvous with Rama

In Arthur C. Clarke’s 1973 science fiction novel Rendezvous with Rama, the beginning of causality is the discovery that an alien vessel is approaching Earth’s system from deep space. This raises the question, “What is the alien vessel for, and why is it coming here?” The rest of the novel unpacks this question.

Clarke’s novel also explores the interesting “what if” concept of an interstellar ark, a traveling megastructure containing a cylindrical mini-world, which uses axial rotation to create artificial gravity. (Nerdy, I know; but I love it.)

Middle: building to a discovery

As the protagonist pursues her plan, she meets growing resistance until something happens that makes further progress impossible. This forces her to look for, find, and commit to a new trajectory.

Progress

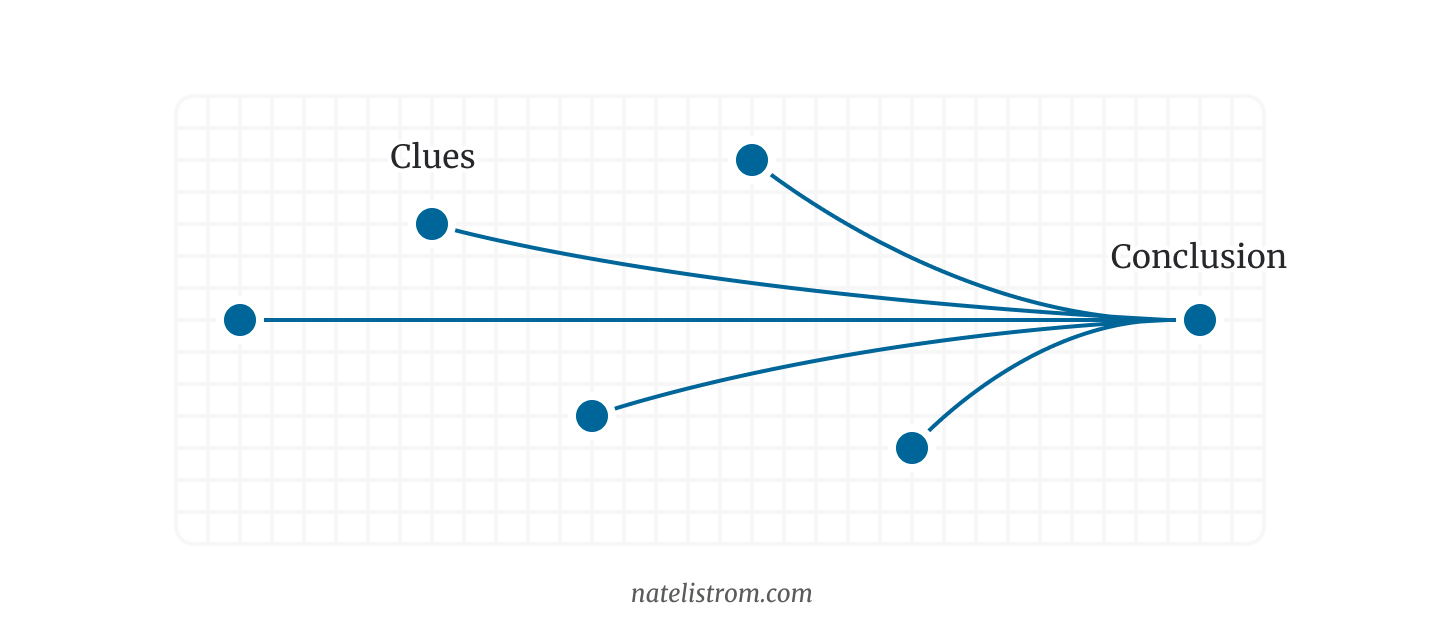

In the progress phase of an idea story, the protagonist goes about discovering clues and attempting to integrate them in a way that answers the question.

Mystery stories tend to have a converging shape. Clues appear in seemingly different places and then, over time, coalesce on the solution. In longer stories, the clues are often misinterpreted at first, and red herrings abound.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

In The Chamber of Secrets, for example, the mystery around the identity of the heir of Slytherin develops in many steps:

- Dobby warns Harry not to go to Hogwarts. (beginning; introduces the question)

- Before arriving at Hogwarts, Harry witnesses minor villain Lucius Malfoy sneaking a book into Ginny Weasley’s things. (Ginny is the sister of Harry’s friend Ron.)

- Harry’s access to the Hogwarts Express train platform is mysteriously blocked.

- Once at Hogwarts, Harry begins to hear a strange voice coming from the walls.

- Harry discovers a magically petrified cat beneath a warning written in blood: “The Chamber of Secrets has been opened. Enemies of the Heir, beware.”

- One of the children’s professors tells them that, according to legend, the Chamber of Secrets contains a monster and can be opened by the heir of Slytherin.

- . . . etc.

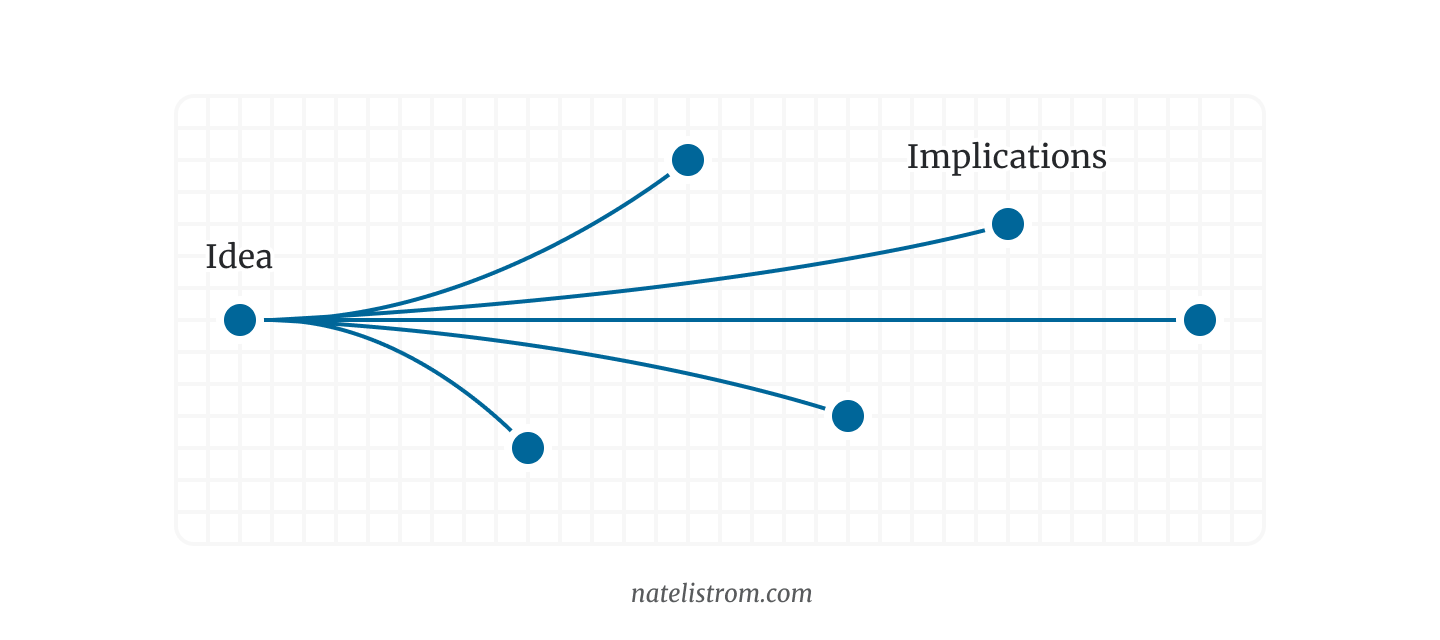

In contrast, high concept, “what if” idea stories seem to have a diverging shape. The core idea is introduced at the beginning instead of being revealed at the end. Then, all the various implications of the idea are explored in different directions.

Rendezvous with Rama

In Rendezvous with Rama, the mysteries of the alien vessel are slowly explored by a human expedition team sent to learn about it and make contact.

My recollection of Rama is a bit hazy, but here’s what I remember:

- First, the team must figure out how to gain entry to the vessel. They discover that the aliens do things in sets of three.

- Once inside, they encounter a vast, dark chamber. They climb down and discover an interior “surface” hundreds of meters below.

- As they explore, they discover a long, straight channel. It turns out to be an artificial light source.

- They discover buildings, an “ocean,” robotic maintenance machines.

- . . . etc.

Disaster

Eventually, something happens that makes it impossible to continue in the current trajectory. In an idea story, this is usually a major revelation that definitively disproves whatever the audience was previously led to believe. The theory, which seemed so promising, abruptly dissolves.

In “whodunnit” mysteries, it’s often the “act two body,” when the primary suspect turns up dead, the latest victim of the real killer. (Kowal)

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

The most obvious example from The Chamber of Secrets is when Harry and his friends take the polyjuice potion and discover that Draco Malfoy, whom they suspected, is not the heir of Slytherin.

High concept idea stories may not have as sharply-defined disasters as mystery stories. Rather than the mystery deepening by debunking clues, it appears that the question is deepened by considering the strangeness of each new discovery. In a sense, each discovery simultaneously brings you closer to a whole understanding and pushes you farther away. The boundaries understanding continuously enlarge.

Rendezvous with Rama

In Rendezvous with Rama, the alien vessel appears to be devoid of activity at first. But then some kind of creature appears to awake and approach. Then the “creatures” turn out to be some sort of maintenance robots.

Each of the discoveries is a minor disaster, changing our understanding of what this thing is all about.

Dilemma

The dilemma in an idea story is about grappling with the possibility that the question may never be answered.

In detective and crime stories, there’s often a scene in which the investigator seems defeated. She doesn’t yet give up (most of the time), but she’s stymied as she racks her brain trying to think of anything she’s missed. Nothing makes sense.

Added pressure during this phase can increase the payoff later.

-

You can sharpen the dilemma by setting up promises earlier in the story, which the protagonist will fail to fulfill if the mystery isn’t solved. The protagonist thinks of a little child who expressed belief in her or a police chief who risked his career to keep her on the case. If she fails, she will let them down.

-

You can sharpen the dilemma with a “time bomb.” (Vogler, Pages 176-177) (Cron, Page 180) The mystery must be solved by a fast-approaching deadline. In police procedurals, this is when the chief comes in and tells the protagonist that she’s being pulled off the case. In thrillers, it’s often when the protagonist learns that the killer has captured another victim and will kill them soon. The time bomb increases the urgency of answering the question quickly, which makes the fact that the case seems unsolvable that much more frustrating.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

In The Chamber of Secrets, the most intense dilemma is driven by the abduction of Ron’s sister, Ginny. This is an event story beat, not an idea story beat. However, if we look closely, there are a couple of idea story elements that contribute to the dilemma:

-

Harry’s mentors, who could help him solve the mystery, are removed. Dumbledore is forced out, and Hagrid is sent to the wizard prison Azkaban. Harry’s friend Hermione, to whom he and Ron look for knowledge, is petrified. (A useful trick for an idea story — strategically remove the character to whom the protagonist looks for information.)

-

Harry’s theories are debunked. The heir of Slytherin is not Draco Malfoy, and the monster the heir controls is not Hagrid’s giant spider.

Harry and Ron are left to solve the mystery on their own, and all their theories so far have turned out to be wrong.

Rendezvous with Rama

In Rendezvous with Rama, the biggest dilemma comes when the alien vessel’s trajectory takes it so close to the sun that the humans must leave. They have discovered some interesting things about the alien vessel, but their investigation is cut off before they can solve the key mystery of why it came in the first place.

Epiphany

The epiphany moment isn’t, itself, the revelation of the answer to the question. Rather, it’s the moment that establishes certainty that the answer will be revealed. Hope is restored.

The protagonist may discover the answer at this point, but it won’t yet be revealed to the audience.

In detective and mystery stories, the epiphany is most often when the protagonist reexamines a previously discovered clue and sees it in a new light. (Often, this new perspective is introduced by an offhand comment from a friend or assistant.) The disparate, seemingly irreconcilable pieces suddenly snap together, and the protagonist sees the whole picture for the first time.

Not all idea stories separate the epiphany from the climactic moment. These can be telescoped into one another.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

In The Chamber of Secrets, for example, the epiphany is sort of implied by convention. Because of genre, when Harry finally enters the Chamber of Secrets, we as an audience expect the answer to be revealed. But there’s not a separate moment in which Harry discovers the heir’s identity before the audience does. Instead, he discovers the answer to the mystery at the same moment we do.

Rendezvous with Rama

Rendezvous with Rama doesn’t have a distinct epiphany moment separate from the climax either. The discovery of the true purpose of the alien vessel’s visit happens as the humans leave the vessel and watch it pass close to the sun, but this revelation is the climax of the idea story, rather than a moment that points toward it.

End: the answer is revealed

In the climactic moment of an idea story, the question is finally answered. (Or, the question is definitively not answered, but in a way that the audience can see was intentional.)

In mystery stories and police procedurals, there’s often a summary explanation of all of the clues and how they fit together.

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

In The Chamber of Secrets, Harry discovers that Tom Riddle, whom he earlier met magically through a diary, is actually Lord Voldemort, the heir of Slytherin. Tom explains how, through the diary, he magically controlled Ginny Weasley and used her to perform acts like writing the message in blood on the wall. Suddenly it all makes a terrible kind of sense. (This sets up for a battle between Harry and Lord Voldemort, but that’s the climax of the event story; the idea story reaches its conclusion here.)

Rendezvous with Rama

In Rendezvous with Rama, we finally learn the “why.” The human expedition watches as the alien vessel dives into the edge of the sun and sucks up energy. It wasn’t coming to make contact with humans at all. It was using our system to refuel before going further on its way to somewhere else in the galaxy.

Rate this note

Read this next

Beginning, middle, and end part 5: Character stories part 1

The key change in a character story is about worldview and beliefs. The beginning establishes the protagonist's 'lie,' and the progress and disaster phases show how that lie is challenged.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.