The map and the mountain: Fifteen core beats of story structure

Summary: Story structure frameworks are like maps. They need interpretation. In this note, I briefly cover the framework I use and introduce a series on how it works.

Last year, I went to Colorado and hiked in Rocky Mountain National Park with my brother. We spent three days in the mountains, rambling up various trails and enjoying the outdoors: the clear alpine lakes, the tall, stately conifers, the occasional glimpses of wildlife.

It was fantastic.

My brother’s in pretty good shape. He hikes a lot. I, on the other hand, spend my days working at a desk. The most exercise I usually get is chasing down a four-year-old at bedtime. So, we needed to be a bit picky about which trails to hike. The park maps helped here. They showed us the length of each hike, the relative gains in elevation, and the features we’d encounter.

To me, plot frameworks like the Hero’s Journey, Save the Cat Beat Sheet, and Seven Point Plot Structure are all like maps. They give you the high-level features, the terrain you can expect to cover.

But the map is not the mountain. It’s a representation. In order for it to be a benefit to you, you need to know how to apply it.

It’s one thing to say, “There’s a ‘turning point’ here.” It’s something else to know what a ‘turning point’ is, why it exists, and what kinds of variations are valid in your current work-in-progress.

Today, I’m going to give you my map. It’s what helped me explore and analyze any number of stories, and it’s what helped me plot my novelette, The Mirror of Tantalus.

But, more important than just giving you another framework (there are plenty of those), in the notes that follow, I’m going to show you how to use Dwight Swain’s scene-sequel format as a tool for interpretation. I’ll demonstrate how it applies it to my framework in a way that you can grab and repurpose with any of the dozens of frameworks out there — or even use to build and interpret your own.

By the end of this series on applying structure, you’ll have a deeper understanding of what story experts mean when they talk about things like “turning points”, “inciting incidents”, and “dark nights of the soul.” And, you’ll have more confidence as you climb your own story’s winding heights.

Ready? Let’s put on good climbing shoes, grab some hydration and protein-rich snacks, and hit the trail.

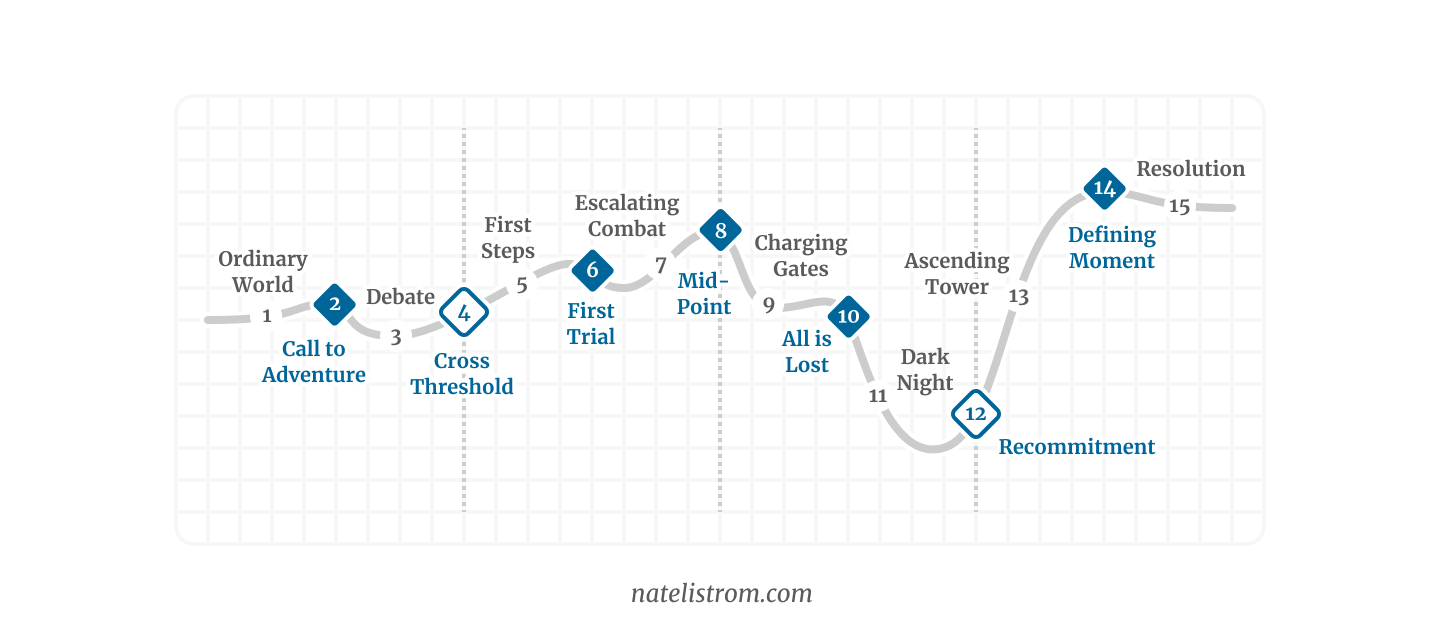

Mapping the Western Character-Event story structure

To get started, here’s a high-level overview of the map. If you’re familiar with popular frameworks, you’ll notice there’s a lot that looks familiar. Where possible, I’ve used terms and ideas that already exist. Why reinvent the wheel? A

I call this the Western Character-Event Story. (Nerdy and academic-sounding, I know.)

- “Western” because although I think this general shape is universal (more on that later), I acknowledge that it’s based on traditions from Western Europe and North America.

- “Character-Event” because the stories that stand the test of time tend to be the ones that feature some kind of internal character transformation, and that’s most often and most easily prompted by external story events. (Idea stories follow a similar shape but tend to appeal to smaller audiences.)

Don’t worry if this sounds too abstract. Just know that many Hollywood, Disney, and Pixar movies use this general story shape successfully, and you can too.

Act I

-

Ordinary World

Your protagonist lives her regular life and pursues her regular goals. Although she doesn’t know it, her worldview is flawed somehow. There’s a lie she believes about herself, which is hurting her. (Weiland, Page 12)

But, she’s settled in her incompleteness. (Mazin) (Hague) Her life may not be perfect — or even satisfying — but at least she’s used to it. She doesn’t realize she, personally, needs to change. (Vogler, Page 121) She likely doesn’t even know that’s possible.

-

Call to Adventure

Your protagonist encounters something that disrupts her carefully constructed stasis. She’s introduced to a goal and offered the opportunity to pursue it. Things are tipped out of balance in a way she can’t ignore. She’s confronted with a choice. (Vogler, Page 11) (Coyne, Page 160)

-

Debate

Your protagonist reacts to the disruption. She wants to go back to her flawed but stable life, but she can’t do that now — not without knowing that she’ll be leaving the new opportunity behind. This creates a dilemma. What will she do? (Weiland, Page 42) (Vogler, Page 131)

-

Decision to Cross the Threshold

Your protagonist decides to accept the challenge, embark on the adventure, pursue the goal. (Weiland, Page 47) (Swain, Page 163) (Yorke, Location 1682) (Vogler, Page 151)

Act II A

-

First Steps in a New World

Your protagonist begins to explore her new situation. She witnesses, for the first time, a new way of being. (Vogler, Page 159) Although she doesn’t yet know it, this new way stands in contrast to — and will eventually confront — her mistaken worldview. (Weiland, Pages 53-55) (Mazin)

-

First Trial

The new world isn’t all roses. There is danger here. The antagonistic force makes itself felt. Your protagonist learns that she won’t be able to simply obtain her goal without friction. (Vogler, Page 160) (Truby, Page 289) (Weiland, Page 91)

-

Escalating Combat

Your protagonist continues to pursue her goal but faces rising resistance. There’s a back-and-forth between setbacks and progress. (Vogler, Pages 176-177) (Truby, Page 48)

Importantly, her tactics to deal with things demonstrate that she is still relying on her mistaken worldview. (Hague) (Yorke, Location 876) (Weiland, Page 56)

-

Midpoint

Your protagonist encounters something that threatens her ability to truly obtain her goal. She may achieve a “false victory” and seemingly reach the objective, (Snyder, Page 84) but it won’t be a victory in truth because she hasn’t yet changed. (Weiland, Pages 70-71)

Nevertheless, at this crucial moment, she does experience a window into the truth, a “moment of acting in harmony with the theme.” (Yorke, Location 1296) (Mazin)

Unfortunately, she won’t yet know how to integrate it, and as she moves on from the midpoint, she falls back on her lie.

Act II B

-

Charging the Gates

It’s game time. Your protagonist has “learned the ropes” of the new world (externally, at least), and she pursues her goal with zeal. But the antagonistic resistance is much stronger now. Every inch is a battle. (Weiland, Pages 66-67) (Hague) (Freytag, Five Parts and Three Crises section) (Snyder, Pages 85-86)

In this phase, your protagonist’s lie begins to consequentially hold her back. Her old way of doing things won’t work anymore. But she doesn’t want to give it up just yet. She keeps trying harder to make it work . . . (Weiland, Pages 67-69) (Mazin)

-

All is Lost

Your story events conspire to disrupt your protagonist’s plan again. But this time, it’s fatal. Everything breaks, and no amount of pushing harder will fix things. The goal is now impossible to reach using the old paradigm, and your protagonist finally realizes it. (Vogler, Page 225) (Booker, Page 57) (Booker, Page 245) (Bork, Page 156) (Weiland, Pages 148-149) (Truby, Pages 294-295) (Snyder, Page 86)

-

Dark Night of the Soul

Your protagonist reels from the blow. She grieves. (Snyder, Page 88)

Slowly, as the reality of her situation unfolds, she discovers that there is only one way to move forward: she must change. (Vogler, Page 207) (Cron, Page 86)

But she doesn’t want to do that. It’s frightening. It means giving up her old self. (Campbell, Page 261) (Weiland, Pages 75-76) (Hague) She’s caught in an unbearable dilemma: embrace the difficulty of change or live with the forever knowledge (and shame) of turning back, giving up on her goal. What will she do? (Mazin) (Phillips, Location 883) (Phillips, Location 2240) (Yorke, Location 615)

-

Recommitment

Your protagonist finally decides to abandon the lie she believed and fully embrace the truth. (Weiland, Page 77) (Truby, Page 295) (Truby, Page 302) (Vogler, Pages 211-212) (Swain, Page 187) (Snyder, Page 89) (Or, in a tragedy, she decides knowingly to double-down on the lie.) (Weiland, Pages 148-149)

Act III

-

Ascending the Tower

Now equipped with the truth for the first time, your protagonist renews her pursuit of the goal. She faces down the forces of antagonism one by one in order from weakest to strongest. (Snyder, Page 91) (Freytag, Sophocles’ Construction of the Drama section) (Yorke, Location 1945) (Truby, Page 300)

-

Defining Moment

Confronting the greatest possible antagonistic force, your protagonist gives herself fully to the truth. (Swain, Page 193) It’s one thing to make a decision at the Recommitment; it’s another to follow through. Here, she makes good on her promise. (Weiland, Page 19) (Phillips, Location 4319)

Through herculean effort, your protagonist “embodies the truth of the theme through action.” (Mazin, Emphasis mine) She defeats the antagonistic force. She obtains the goal. She settles the conflict. (Yorke, Location 643) (Truby, Page 300) (Weiland, Page 92)

-

Resolution

Your protagonist has learned to live fully in the truth. In some significant way, her life now is different compared to what it was in the Ordinary World, and we get to see that illustrated in the events of the resolution. (Truby, Page 304) (Vogler, Page 249) This proves with finality that the transformation was real and enduring. (Weiland, Pages 137-138) (Phillips, Location 4321)

Life has returned to balance, but in a new, better place.

More to come

Now you have the high-level map. In future notes in the series, we’ll dive deeper into each one of these and look at examples of how they play out in working stories.

But remember, a map needs interpretation. The most useful thing I can give you is not descriptions of the beats, but a tool for getting at the underlying why.

In the next note, we’ll start to unpeel the onion on exactly that. We’ll look at Dwight Swain’s scene-sequel format and discover why it has become my go-to tool to unlock how story structures really work.

Onward!

Rate this note

Read this next

Use one scene-sequel cycle each act

In a Western Character-event story, the scene-sequel cycle repeats three times on the act level. Using 'Star Wars: A New Hope' as an example, we examine how that works and how you can use it for your stories.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.