Shinichi Suzuki and the three domains of mastery

Summary: An exploration of the interaction between talent, education, and skill.

“Knowledge is not skill. Knowledge plus ten thousand times is skill.”

— Shinichi Suzuki

I have been thinking about this quote for a long time. It sums up an ideal I subscribe to. I’m enamored of the idea that mastery of a skill comes from having done something over and over and over again, that there’s tremendous value in pouring yourself into a worthwhile pursuit, that hard work pays off in the end.

It may be helpful to think of mastery of a skill in terms of three basic domains: talent, education, and experience.

Talent

Talent is the domain of intuitive mastery. It is the hardest (and easiest) mastery to achieve, because it is something we are born with. We just get it, and then we often feed and develop it as we grow older.

Talent provides the baseline — the natural starting point for mastery. It gives some people a head start in a particular area. It also provides the ceiling for mastery. Some of us, no matter how hard we work, will never attain the heights that others do. We as humans simply do not have limitless ability. At some point, all of us will reach the end of possibility.

Talent is, then, the domain of mastery that sets the brackets. It establishes the bottom and the top of what is possible. We merely have the freedom to move around within those limits.

Finally, it’s interesting to note that we have almost nothing to do with whether we have talent or not. We also have relatively little to do with whether or not we give talent to others. While it’s true that parents may transfer some aptitudes to their children — creativity, analytical ability, etc. — this is somewhat hit or miss. We haven’t (yet) perfected a method of giving our children specific abilities.

Talent is still something that is largely beyond our control. It is a gift that comes from outside of us.

Education

The second domain of mastery is education. If talent is intuitive mastery, education can be thought of as intellectual mastery.

Education contrasts sharply with talent; in fact, the two are nearly opposites. While talent is non-transferrable, one of the signature traits of education is its essential transferability. It is the gift we give one another.

If we think of a scale, which talent provides brackets for, education can be seen as a metric of potential on that scale.

By itself, education doesn’t actually change a person’s abilities. What it does offer a person is opportunity.

Which leads us back to Suzuki. Education is a kind of knowledge, but mastering that kind of knowledge alone is not skill. Intellectual knowledge plus “ten thousand times” — that’s what skill is.

Experience

What Suzuki was talking about — and what I as a student of craft am here focused on — is the third domain of mastery: experience.

Experience is the great mover. It is the main thing — sometimes the only thing — that separates the masters from the rest of us. It is the thing that fills up all of education’s potential with realization.

Interestingly, experience also opens the way for new education. While talent is mostly static, education and experience tend to work together in synergy.

Have you ever noticed how a boss’s or mentor’s instructions are sometimes incomprehensible to you until you have done a certain task for a while? Then, all of a sudden, the light comes on. A new mental connection is made. The thing makes sense. As learning paves the road that experience walks, experience opens the door for additional learning.

Like talent, we can’t give experience to other people. It’s non-transferrable. However, unlike talent, we can give it to someone: experience is the gift we give ourselves.

We are ultimately accountable for our level of experience. This is not true of the other domains. It would just be silly to try to hold a person responsible for his or her level of talent. To an extent, we can’t even hold one another responsible for education — at least, not beyond the opportunities that were offered to us. But experience depends completely upon our own willingness to apply ourselves.

Granted, some people — a special few — are born with so much natural gifting that they don’t really need education. They intuitively grasp what it takes the rest of us years of education and experience to lay hold of. But — and this is an important but — amazing as talent is, it should never distract us from the fact that education and experience do accomplish their work. It’s an old cliché, but a true one in many ways. Lackluster talent combined with hard work is often far better than superb talent with laziness.

For us regular folks, mastery takes time and a lot of hard work, but that’s what skill is. Skill is not just knowing. Skill is knowing by having known — known by experience. It’s having gone through a process over and over and over again — ten thousand times if need be — until it is perfected.

Are you hoping to master a skill in your life? Get to work! Gain experience. Of the three domains of mastery, it’s the one you’re responsible for.

It’s the gift you give yourself.

Notes

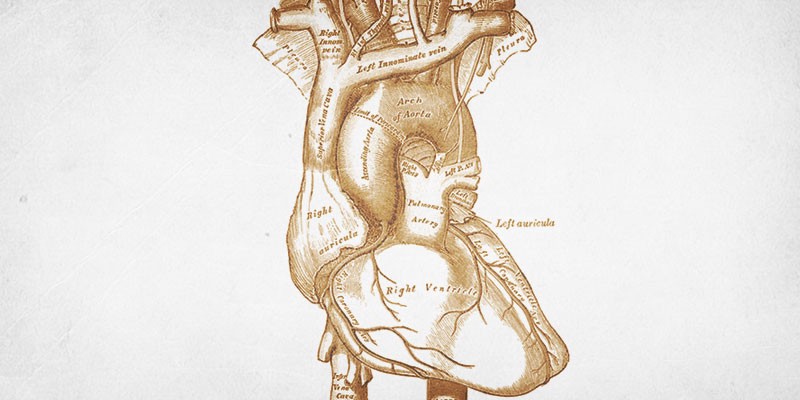

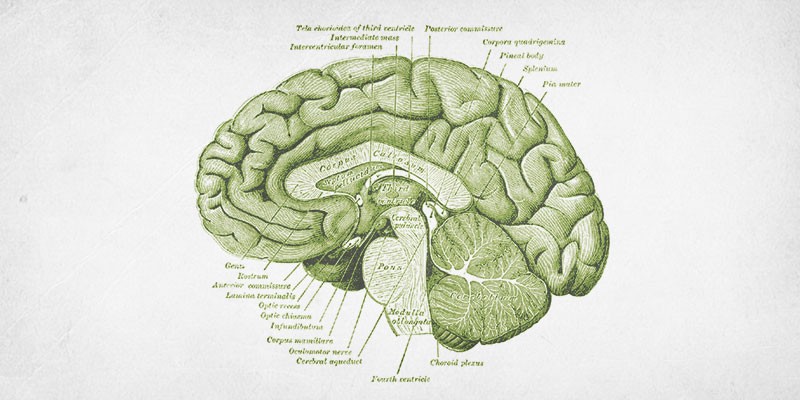

The body illustrations in this post originally came from the Wikimedia Commons collection of plates from Henry Gray’s 1918 The Anatomy of the Human Body.

Rate this note

Read this next

The right 15%

To be world-class requires focused effort and persistence in the right direction.

Level-up your storytelling

Understand how stories work. Spend less time wrangling your stories into shape and more time writing them.